Home Gardens of Haberfield sought to explore the nexus between gardens, place-making and senses of belonging and community and to document gardening practices.

Our methodology for this project included iterative walks to help us identify human and non-human participants and issues of concern. As we walked we also documented gardens and streetscapes with photography, and took notes. This initial research helped us formulate a set of questions to conduct oral history interviews with 9 gardeners. These questions explore three conceptual areas: the cultural history of the gardeners and garden, the actual garden, as design and gardening practices, and the social encounters and relations generated in and by gardens.

The oral histories were then transcribed, content coded and edited a first time. We sent them to the people we interviewed for their edit, as we take the view that that oral histories are about co-creation, and it is important that our co-creators recognise the tone and the voice, as well as content, as their own. Finally they are published here.

In this process we learned that gardens as complex entanglements of plants, humans, animals, natural elements, weather, resources, soil, fungi, bacteria mutually affecting and affected by gardeners. Also they are not simply natural oasis in the built environment: they are intensely social sites.

It produced 4 key findings.

1. Collective Heritage

The idea of heritage in Haberfield (and elsewhere) is collective, dynamic, and responsive. It is not just about individual houses and streetscapes, it is about a sense of locality that is produced through social relations and everyday practices.

Haberfield is on Wangal and Cadigal land. British settlers arrived in the early 1800s, and Dobroyde estate was established in 1805. One of the estate’s daughters married a Ramsay, and they established orchards, streets and several houses, including Yasmar (Ramsay back to front). In 1901 Richard Stanton, who was a developer, bought a parcel of land, contracted several different architects working in what is known as Federation style and established the first garden suburb. When people talk about Haberfield’s heritage this is the period they generally refer to. After WW2 migrants from South Europe, mainly Italian, but also Greek, moved to Haberfield, and they brought different ways of gardening. Now Haberfield, like much of the inner suburbs of Sydney, is gentrified. Several participants expressed the fear that with the arrival of a middle class that has to work very long hours to pay huge mortgages and does not have time for much else especially gardening, Haberfield’s history and heritage will soon be lost. Others more optimistically pointed out that young people bring in new gardens and new ideas, and that many are actively interested in vegetable gardens as a lifestyle choice.

This suggests the necessity to document changing ideas of heritage longitudinally.

2. Affective Gardening

For individuals, gardens contribute to emotional and physical wellbeing, activate memories, produce new memories and produce an important sense of belonging.

All participants spoke of important personal connections to love of nature and the Australian bush and family gardens as the background to their own gardening practices.

For some designing, experimenting, choosing certain plants in the garden is important not just for physical and mental wellbeing, but also for cultural wellbeing. By this we mean the sense of being part of a historical continuum (which you may call heritage) through everyday practices, such as gardening. Especially in consideration of WestConnex’s destruction of heritage homes, gardening is seen as a way to resist the erosion of cultural, as well as material, heritage.

There are different types of gardens, and several of the gardeners we spoke with would like to see the documentation of Italian gardens, which, they fear, are disappearing as first generation Italians stop gardening. We also need to point out that there are different types of Italian gardens, and that Italian Australian gardens may be different from say, a Sicilian productive garden.

This finding suggests to conduct an audit of Italian gardens in Haberfield.

3. Gardening is about sharing

The Haberfield Association runs a successful Gardening Competition. This fulfills an important role, that is more about collaboration and sharing and socialising than it is about competing.

Vincent Crow, historian, taught us about the fundamental principles of Federation design: low fences opening on gardens with beds of colourful annual flowering plants, that would not crowd the view of the house. These gardens, together with the trees planted on the street shoulder to create a canopy, gave a sense of aesthetic continuity and community to the street.

This idea is still valid: people do like to peer into other people’s gardens and gardening generates social relations. Sometimes they are good, sometimes they are tense. Some of our participants described difficult ‘fence relations’ with their neighbours. These difficulties generally derive from different ways of understanding gardens and their functions, and different tastes in gardening that are culturally specific.

Italian vegetable gardens for instance are described by non-Italians as ‘neat’ as opposed to the curated disorder of cottage gardens and the ornamental Federation gardens.

This, as it was pointed out in several occasions, is reflected in the competition, were Italian gardeners enter and never win the main prize, because the main prize is for ‘heritage’ gardens, and heritage in this formulation means Federation.

We suggest that IWC supports the gardening committee to expand the competition into multiple events and a creates a community garden site in Haberfield.

4. Gardening as Civic Attachment

For Haberfield gardeners, environmental stewardship is an important aspect. Designing, maintaining and sharing gardens is a way of supporting and learning about other species in the city, such as birds, insects, and of course, plants. One of the recurrent themes in our interviews is the importance of gardens in the ecology of the suburb.

Caring for one’s own garden is seen as a significant contribution to the environment. Gardeners spoke of the joy of maintaining ‘inherited trees’ visited by native wildlife for instance, especially birds. Of planting trees to attract birds, flowers to attract bees, we have seen three bee hotels.

Rainwater is collected, and foods craps are recycled in compost heaps.

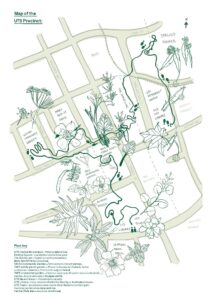

We have a final couple of suggestions (this is the map of the gardens that entered the gardening competition in the past 10 years or so): 1 Leverage and make visible existing environmental stewardship examples to expand the concept of gardening in IWC. 2 Update the identity of the Garden Suburb to include these practices.

0 Comments