Shannon Foster, University of Technology Sydney; Alexandra Crosby, University of Technology Sydney, and Ilaria Vanni, University of Technology Sydney

Sydney’s Green Square is one of Australia’s biggest urban renewal projects. But it’s much more than a construction site. First Nations people know it by another name: nadunga gurad, or sand dune Country.

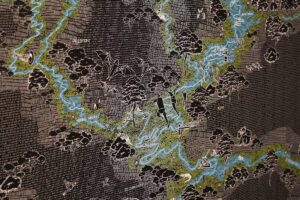

For millenia, the area has been known for its nattai bamalmarray: freshwater wetlands and seasonal ponds. This Country has always been an important refuge along the Songline routes that connect War’ran (Sydney Cove) to Gamay (Botany Bay).

To existing residents, Green Square is home. It’s also a place to walk, visit parks, shop, and talk to neighbours, shopkeepers and tradies.

But it can be hard to see the “green” in Green Square. It’s a disrupted place punctuated by huge pits in the ground, roadworks, scaffoldings, barriers and cranes.

We’ve been working on connecting residents, workers and visitors to the local environment. We hope our project becomes a template to help anyone engage more deeply with their neighbourhood.

City of Sydney

An atlas for change

Green Square spans the inner east Sydney suburbs of Zetland, Beaconsfield, Rosebery, Alexandria and Waterloo. In 2020, the site was home to 34,000 people and this number is growing rapidly.

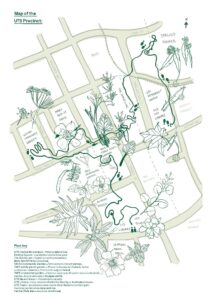

During lockdowns last year, we and the charity 107 Projects sought to connect residents, workers and visitors to nature and people in their suburb. It involved workshops, walks and a map for self-guided tours. We also collected stories in a book, just released. It includes stories about:

- a community garden group

- beekeepers and honeymakers

- public art and verge gardeners

- artists

- Australia’s leading food rescue organisation.

Atlases have historically been, and continue to be, tools of colonisation – cataloguing and archiving the status quo.

But done right, they can also help us understand places in new ways. In Australia, this includes recognising we are always on Indigenous Country.

In that vein, our atlas includes an important contribution by Shannon Foster, a registered Sydney Traditional Owner and local D’harawal eora Knowledge Keeper.

Jo Kinniburgh

Ngeeyinee dingan duruwan bata

Foster tells how, amid dense urban development at Green Square, unique plants from ancient ecosystems still emerge from undeveloped gullies.

These include paperbark trees, casuarina groves, clumps of kangaroo grass and lomandra, and regenerated areas of Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub.

As Foster says in this edited extract:

One of my earliest memories of learning culture from my D’harawal eora father was about understanding plants and what you could and couldn’t eat. I was always amazed to realise that you could actually live off the gardens and earth around you.

Today, one of my favourite edible plants is bamuru (kangaroo grass), not just because you can make a delicious, gluten-free, light and tasty bread from it, but because it represents the un-forgetting of knowledges and stories that have been silenced and, sometimes, erased from our lives.

There are places across Sydney Country, especially on abandoned and neglected land, that bamuru and other edible crops like bundago (native daisy yam) flourish again. These plants begin to grow in vast fields, echoing their ancient, agricultural past and the careful management of Country by local custodians like my D’harawal eora family.

The awakening of these remnant crops is a reminder that Country is its own archive, holding seeds and stories as evidence that we do indeed exist and that we have long and complex relationships with Country that can never be erased.

Now, as I walk the streets of Green Square, I look for signs of old Country breaking through the centuries of colonial development.

I dream of this place as it was, sand dunes and wetlands, galumban gurad (sacred Country), and I marvel at the fragile seedlings who, against all odds, break through the oppressive concrete and pavers to stand tall, once again, with Country.

I also honour the same spirit in my elders and ancestors who have raised me to understand that it doesn’t matter how much concrete is laid down, Country is still here and is still nurturing and sheltering us, just as it always has been and always will be.

– Ngeeyinee dingan duruwan bata (May you always taste the sweetest fruit).

Always was, always will be

Foster reminds us no matter how much we build on Country, it has always been – and remains – vital to life and culture for local custodians.

More broadly, the atlas aims to show we can improve city life and the urban environment – just by how we interact with one another, and treat the plants, animals and insects around us.

Ilaria Vanni

If this idea appeals to you, download a free copy of the atlas and try these activities to help you “tune in” to your local area:

- find out whose Country are you on

- save and exchange seeds from native plants and heirloom food varieties

- get to know your local plant species, especially the endangered ones

- make and maintain a verge garden

- start or join a community garden

- forage for wild foods, such as edible weeds

- conserve water

- create habitat for urban wildlife

- spend time at nearby natural places such as ponds and parks

- cut waste, to reduce pressure on city services and the planet

- look for trees providing shelter on hot days.

These small, slow actions help create connections to nature and place, and opportunities to meet and share with people in your community. These connections are vital to overcoming the downsides of urban renewal.

And as we remake urban places, we must remember: our neighbourhood always was, and always will be, unceded Aboriginal land.![]()

Shannon Foster, D’harawal Knowledge Keeper PhD Candidate and Lecturer UTS, University of Technology Sydney; Alexandra Crosby, Associate Professor, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney, and Ilaria Vanni, Associate Professor, International Studies and Global Societies, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

0 Comments