Gardens, verges and parks are sites where individuals can become involved in forms of ‘civic ecology’.

We borrow this concept from Krasny and Tidball (2012, 2015a, 2015b), who in their book Civic ecology: Adaptation and transformation from the ground up concentrate on ‘hands-on stewardship practices that integrate civic and environmental values’ (2015a xviii). This definition is key to understanding how place is made in Australian cities because it brings together social, cultural and environmental aspects in the study of cities and ecosystems.

Krasny and Tidball, however, extend the scope of civic ecology suggesting that it ‘also entails applying an ecological perspective to understand how people, practices, communities, and the environment interact’ (2015a xiii). To do so they identify ten principles of civic ecology, showing how it emerges, what practices it calls for, and how it connects to organisations, businesses and government. In summary, civic ecology emerges in places that have undergone or are undergoing disruptive change, out of a love for nature and attachment to place that leads to stewardship practices. These practices bring together social, cultural and environmental factors, and in so doing create communities. Civic ecology draws on human and more-than-human memories (such as for instance the ‘biological memories’ – ‘the seeds, the wildlife, and the ecological processes that are maintained in an ecosystem and that determine its future possibilities’ 2015a p. 7) to regenerate place. Civic ecological practices also produce ecosystem services, foster wellbeing and opportunities for learning, and establish networks with organisations and government bodies (2015a pp. 7-10). Finally, to think about these practices with an ecological perspective means to understand how they are part of cycles of renewal and destruction, and to investigate the role of policy makers in cultivating civic ecologies.

Civic ecology is a fruitful concept for thinking about heritage because it brings individual, community, social and cultural elements together with place and the natural environment. A key aspect of civic ecology is that it establishes a nexus between local culture and the urban environment taking as examples self-organised, locally driven, networked stewardship initiatives including community gardening, conversions of industrial areas to nature centres, rooftop gardens, and parklands (Krasny et al. 2015b).

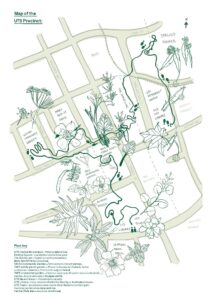

Focusing on this aspect enables us to explore how local cultures and concerns shape civic ecology practices. One of our key research questions is how the concept of Civic Ecologies applies to Australian cities and specific precincts like Green Square. In Australian cities heritage and identity are often defined by ideas of green space, sustainability, and gardens, and also local government, such as the City of Sydney, are involved in creating some forms of civic ecologies. As a consequence, environmental stewardship practices such as gardening or caring for trees on the streets’ shoulder, are already part of local cultural practices and connect to urban planning strategies. In other words, grass root practices and local government work have several overlaps. Drawing from this, in our projects we foreground the role gardening, gardens and plants play in the definition of localised civic ecology practices and we also explore the amplification of these through local governmnet.

Marianne Krasny is now Director of the Civic Ecology Lab in the Department of Natural Resources at Cornell University, specialising in community environmental stewardship and environmental education in urban and other settings in the US and internationally.

Krasny, M. E., & Tidball, K. G. (2015). Civic ecology: Adaptation and transformation from the ground up. MIT Press.

Krasny, M. E., & Tidball, K. G. (2012). Civic ecology: a pathway for Earth Stewardship in cities. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 10(5), 267-273.

0 Comments