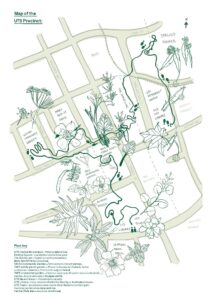

In this post, we reflect on the place-based design methodology involved in making Water Stories. Grounded by Doreen Massey’s definition of place, the project combines a set of ethnographic, historical and visual methods is applied to answer two research questions.

The first question is broad and applies to many of our projects:

As researchers working across social sciences and design, how can we make visible and present socio-environmental entanglements in cities to generate more meaningful connections to place?

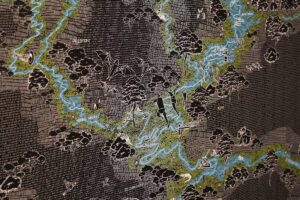

For Water Stories, we read these entanglements as ‘trajectories’ and ‘throwntogetherness’ to trace how water has been perceived at Green Square as well as to imagine how stories of water could help to orient people towards practices of care and stewardship.

A place-based methodology begins with place. So, let’s first unpack the concept of place. As a site of urban redevelopment (since the 1990s) Green Square is perceived as a place in becoming, built on the tabula rasa (Foster and Kinniburgh) of the post-industrial heartland, unfinished and largely un-storied. This development and future-oriented imaginary contributes to an erasure of socio-environmental processes and memories of place and with them to the erasure of connections between people and their environment.

The ‘stories’ in Water stories refer to geographer Doreen Massey’s definition of space. In her 2005 book For Space (Massey, 2005, p. 9), Massey proposes a three-fold definition of space: as made of and by interrelations (or trajectories) bringing together different scales, from the global to the intimate (for instance, exotic plants travelling the globe as seeds then growing in a local pond); as product of multiplicity and coexistence of differences (the presence in the same pond of native plants, exotics, plants part of a landscape design, spontaneous plants, ducks, gambusia, koi liberated by someone, plastic wraps of a global brand of lollies, mono-use facemasks made in Australia from imported materials); and as always changing and in the making (the transformations of the pond with seasons, climate change, council work, surrounding changes to the landscape, people visiting).

According to Massey, a particular collection of diverse trajectories (or throwntogetherness) that generates a here and now constitutes place.

The second question is more focused and generated the creative and public-facing outcomes of this project, such as the website.

We know how to theorise entanglements as trajectories, but how can we guide people to experience place as trajectories in order to encourage care and stewardship?

To answer this question, we took up the concept of portals and applied it to the StoryMaps interface. We worked with knowledge holder Shannon Foster to respectfully consider Country in the design of the stories. And we collaborated with illustrator Ella Cutler to come up with illustrated responses to the visual material, and a look and feel for the website. We also worked with colleagues from Interaction Design to think through how users of this site might interact with unconventional ‘maps’ of a place that were more likely to get them lost than efficiently navigating Green Square.

Interdisciplinary methods

We are trained in design, history and ethnography, and we also read widely in geography and environmental humanities.

Like many others, we are drawn to the inventive methods and radical methodological openness (Shaw, DeLyser, Crang 2015, 212) of cultural geography to research the messiness of place.

To make present the multiple stories so far of Green Square we take Tim Cresswell’s (2012) invitation to consider place as a living archive as our point of departure. The first one is to accept its incompleteness and messiness and read it ‘against the grain’ to find unofficial stories hidden in its gaps. This means mapping what is not included in the archive and understanding what these gaps mean (for instance Indigenous water stories, histories other than ‘the industrial heartland’),

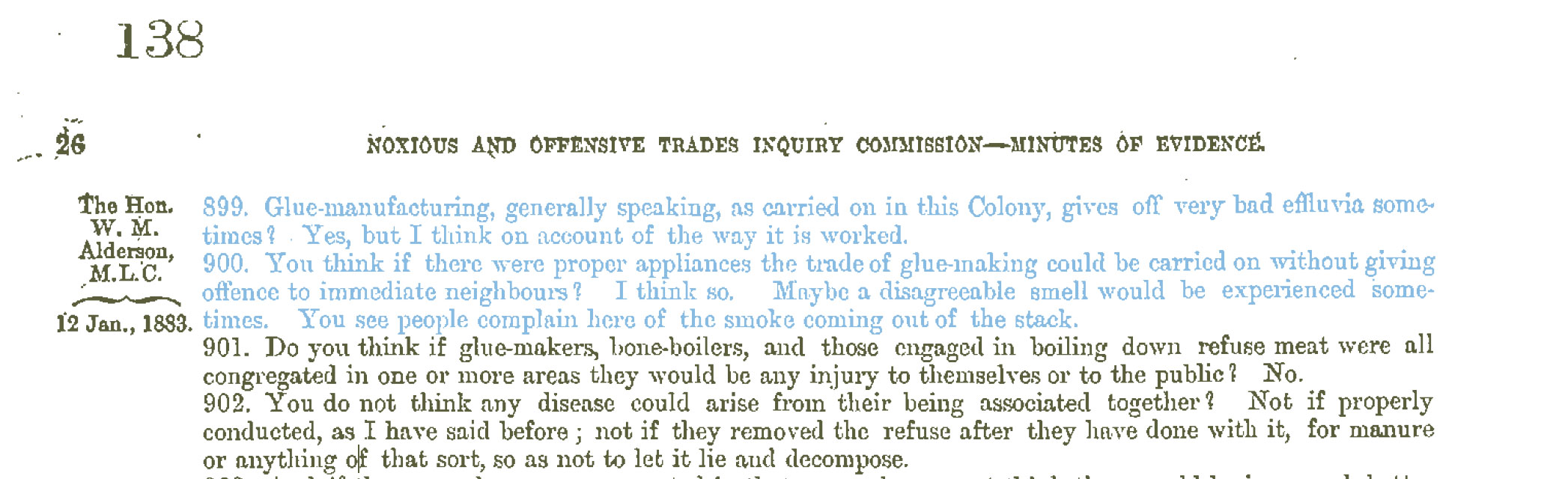

Archival methods

This project involved many hours spent deep in historical archives such as SLNSW and TROVE. We were looking for evidence (text and images and relations between them) of specific events, characters, and practices that grip wider historical circumstances and transformations. Through the portals of the Green Square imaginary, we move between different scales of observation, remixing close-ups on the local, like a newsletter about the Rosebery population of Green and Golden Bell frogs from FATS, and long shots on trajectories in and out of place, for instance the history of the Threatened Species List of NSW.

Ethnographic methods

Walking and observing in Green Square is one way to read against the grain. Looking closely, iteratively, and collaboratively, we can see plants from ancient ecosystems emerging in the midst of urban development. For Water Stories, as well as following waterways on new paths, we drew on data gathered through ethnographic research in a previous project, The Green Square Atlas of Civic Ecologies.

Wetland plants like swamp lilies, paperbarks, and rushes mark the presence of underground water in streets, parks and gullies. Indigenous environmental and cultural knowledges of Green Square, absented in the archive, are alive and well, and we need to listen to them.

Cresswell also suggests to read the archive ‘along the grain’, to understand the historical power structures that shape the archive (such as the affective and aesthetic politics of luxury apartments advertising in the contemporary emplaced archive of Green Square).

We hope you have enjoyed seeing below the surface of Water Stories, how we both implemented and developed a place based design methodology . Touching on Sustainability & interdisciplinary methods.

We acknowledge Green Square as sand dunes and wetlands Country, midway between Kamai and War’ran. I acknowledge all Aboriginal peoples, Gadigal D’harawal eora, Dharug, Bidjigal, Wangal, and more who have cared and care for this Country. I pay my respects to Elders and Knowledge Holders, past, present and emerging, and I pay my respect to Country, and to the plants, animals, humans, sky, air and water and their interrelations.

REFERENCES

- Cresswell, Tim. 2012. ‘Value, Gleaning and the Archive at Maxwell Street, Chicago’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37: 164–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00453.x.

- Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: Sage.

- Foster, S., Paterson Kinniburgh, J., & Country, W. (2020). There’s No Place Like (Without) Country. In Placemaking Fundamentals for the Built Environment (pp. 63-82). Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

- Shaw, W. S., DeLyser, D., & Crang, M. (2015). Limited by imagination alone: Research methods in cultural geographies. cultural geographies, 22(2), 211-215.

0 Comments